On the next platform the crowd was pushing to get close to the doors when the city train came to a stop, so Anna hurried along to the front cars, and squeezed into one just as the doors were shut. Next to her stood a tall young woman in a slim coat.

“Pardon me,” said Anna, thinking she had bashed her with her knapsack.

“No, I’m fine,” said the woman. “Do you want to try and shove it around the corner in there?”

She looked at Anna.

“Canada! What are you doing here? I mean, I haven’t seen you for such a long time.” They hugged. Gingerly. Anna extricated herself.

“Careful there. I’m probably covered in soot and machine oil. You look wonderful. Let’s see, last time we ran into each other, you had just got engaged to a U-Boat officer, but then your family moved.”

“Yes, my father’s office was bombed and we had a chance to get a small place near the new location out in Dahlem. So that’s where the three of us have been hiding out. My parents are getting ready to go home soon.”

“I’ll bet they can’t wait to return to a peaceful life,” said Anna, “what a nightmare it’s been for your whole family.”

“Yes, and they will be returning alone,” she said slowly, “without my brother. You heard, of course, that he was drafted last fall?”

“Oh, no, I — I, we hadn’t heard.” Anna dreaded what was to come next.

“The government argued that, under German law, Dirk was a German citizen, because my Dad never took out Canadian citizenship, and so Dirk had no choice. They let him join the navy at least. That’s where he wanted to serve. Last December he left on his first mission on a mine sweeper, and two weeks later he was gone.” Alma’s eyes filled with tears.

Anna couldn’t speak. Alma swallowed.

“My mother. She is looking for answers, wants to know why she lost her son for someone else’s cause. Keeps thinking she should have done something to prevent this, but there was nothing to be done. My dad tried. But now they just can’t wait to get out of here, you know.”

“I don’t blame them, don’t blame anybody who wants to get out of here. It’s a cemetery without the peace. How about you? Aren’t you going with them then?” Anna had heard a rumour that her fiancé’s boat was missing in action.

People were pushing past them at the suburban stops, tired, worn-out men and women, and children coming home from school.

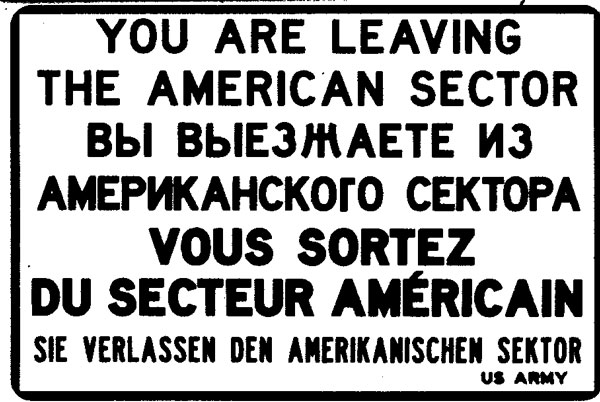

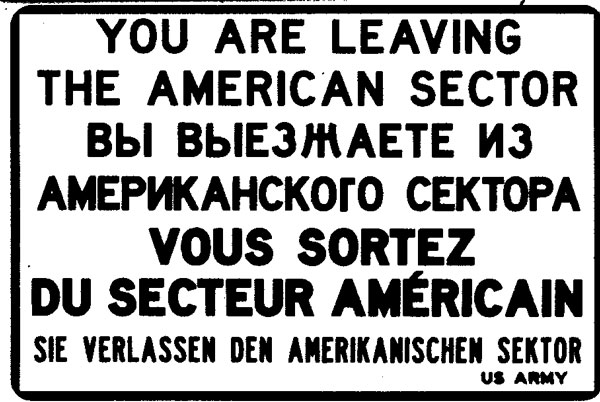

“I started working for the Americans,” said Alma. “They badly need people fluent in other languages, and particularly in writing, so with my English and French I was hired by the administration to work in liaison, for the joint commission. It’s a good job, well paid, and interesting. When I receive definite word on what happened to my fiancé, then I’ll decide what my options are. By the way, I’m going out to the old neighbourhood to pick up a small suitcase that we left with a neighbour. So we are going all the way to your house together, to the corner. Where have you been just now? What’s this about soot and machine oil on your clothes?” And Anna told a short version of her story.

When they left the railway station, Anna noticed the change in the environment. The square by the church had been cleaned up, damaged stores repaired and the window panes had all been replaced.

Soon she would discover that American troops elsewhere in the city walked with an awesome gait of entitlement, likely akin to that which German officers had been accused of during the occupation of France.

Their suburb was in the French sector, though, military vehicles passing to and fro featured French license plates, and no one walking about in the streets appeared to be afraid. There were long line-ups in front of two stores, to be sure, but Anna saw at once that a semblance of normal life had been achieved since their departure in late spring.

Canada wanted to know how it had gone in these parts, but said Anna shouldn’t feel obligated to talk about it, if she preferred not to.

So Anna related the funny story of how she had sneaked off into the woods very early one morning to collect mushrooms after the rain, and had been followed by a shy young Soviet soldier, who suddenly appeared out of nowhere and asked in halting German what she was doing, then helped find some mushrooms. He had produced a photograph of his German girlfriend, a freckle-faced girl in Hitler Youth uniform, and pointed backwards, presumably in the general direction of the Oder river, where he was stuck, along with several Soviet armies, for weeks, until the final assault on Berlin on April 16.

He pressed the photograph to his uniformed breast and proceeded to invite Anna to become his next girlfriend, but she remembered just in time what some of the women had advised in a line-up the day before, and told him she was “sick.”

“Frankly, I have no idea what exactly they were talking about, but it sure worked like a charm. He evidently knew, and he bolted, ran like a rabbit,” Anna said. Her friend laughed.

“Thank goodness,” she said. “My Dad had a Canadian flag. He displayed it outside the window when the first troops moved in, and it may not have scared them but it had a similar effect.”

When they reached the corner, they exchanged telephone numbers scribbled on small pieces of paper, and hugged, and waved and walked out of each others’ lives forever.

“Anna is here, Anna is home!” Foffie shouted and jumped up and down when he saw her approaching. Korinna came to the gate and helped Anna with the knapsack.

“Just in time,” her sister mumbled soberly, “our mother has taken to ambushing neighbours with a toy pistol.”

“WHAAAT? What are you talking about? Slow down, what—”

“Last week. She stood behind a birch tree in the park over there and pointed a toy gun at the neighbour when he came home at night. He didn’t recognize her and beat her up. So be prepared for some bruises on her face.”

“Why on earth would she do a thing like that?” said Anna.

“Search me. She said he had been smuggling guns and was endangering the entire neighbourhood. Total nonsense, of course. But she believes this, will tell you all the details, if you let her. Also, be careful when you hug her. She has boils on her back.” Korinna pushed open the door.

Mother stood with her hands crossed over her breast and beamed at Anna. “My big girl! I knew you would be back. Where is Nadja? What took you so long?”

Anna set the knapsack on the kitchen table, embraced the three, and unpacked Tante Marianne’s treasures. There was butter and cheese, rice, pumpernickel and honey, corned beef, sausages, powdered eggs and milk powder, tea and lentils, and a bag with apples and pears. There were also two big chocolate bars for the children. And shoes for Foffie.

“Where does my sister get all these — did you bring any sugar?”

“I thought so,” said Anna, producing a small packet.

Mother’s eyes were round and anxious, lest these were stolen goods, likely to be retrieved any moment by their rightful owner.

“The mail will soon be working,” said Anna, “and then they will send more things to help us out.”

“It has just started moving,” Korinna announced. “But it’s a joke. People are receiving postcards sent ten months ago, ancient invoices and stuff like that. Letters from people who died long ago. It’s terribly sad, but at least it’s getting underway now.”

A pretty young woman stuck her head in the door and said she was leaving now, and would Korinna please give a message to her sister?

“Who was that?” Anna asked.

“A whore,” Mother announced, with a fierce look on her face.

“Will you stop that?” said Korinna impatiently, “she is NOT a WHORE. Marguerite works for a French officers’ casino a few blocks from here. She and her sister are renting two of our upstairs rooms. They are trying to put their lives together again, and they are nice, brave women.” Korinna stomped out of the kitchen.

Foffie had permission to eat a third of his chocolate and was happily munching. Anna picked him up and swung him in a circle. He was light as a feather.

“I want to take a bath, Mother. The gas is working now, isn’t it? There is warm water? We’ll talk later. There is so much to talk about, but I feel filthy and tired right now.”

At no time had Foffie complained he was hungry in these bad months, but his sisters had often found him in the kitchen, checking the stove to see if anything was cooking. Since ration cards had been introduced people were still hungry, but at least there was now a sense of predictability that something edible could be purchased at given times. Two days after her return Anna actually had to call Foffie in for dinner. He was playing in the newly cleaned up sandbox, talking with Uncle Wernig, who looked much improved since she had seen him last. She walked over.

“Thank you again, Uncle Wernig. Our father sends his thanks and best regards. You can imagine what it was like when we surprised him at my aunt and uncle’s place. He had feared the worst, of course.”

“And he sent me a present and a chocolate,” Foffie shouted.

“How is it going at YOUR place?” asked Anna. And learned that Uncle Wernig had been offered a job in an architect’s office, his line, and he was gratefully accepting it.

War had ended in Germany on May 8th, 1945, more than five and a half years after it had been started. The guns were silent, the dead buried, and the rubble was being cleared away by thousands of women, brick by brick, saving as many reusable ones as possible.

And yes, they needed Uncle Wernig to work in an architect’s office: the repairs were underway. Soon rebuilding the country’s towns and cities would begin. Slowly, but the process would be underway, and what a precious, hopeful period that would be for all who had survived!

Those who had not, died believing this to be the last such unspeakable horror, just like those walking wounded from all the armies, who survived WWI.