On the way home from school one afternoon in May, Anna noticed two young people rollerskating in her street, two young people she had never seen before. They were very good, neither tipping nor wiggling, nor putting their arms out for balance unduly. The girl was about sixteen, tall, with thick brown hair done at the back in a ‘Mozart-braid’. The younger boy looked about a year or two older than Anna. They were talking with each other, but Anna couldn’t understand at first what they were saying.

“You have to watch your right foot,” the girl said in English, “it has to turn more than just sideways to complete that circle you want. YES, that’s it. That’s good!”

Anna stopped and leaned against a birch in front of a neighbour’s house.

“That looked very fine,” she said in English and smiled. The two sailed effortlessly towards the curb and stopped without scraping.

“Hullo,” said the girl. “We’re your new neighbours. We live just around the corner up there. My name is Alma and this is Dirk. But we can speak German as well.” And she switched to a slightly hesitant high German. “We’re Canadians,” she said. “We came here to stay for a year.” Anna stuck out her hand.

“I’m Anna. You must be the kind ‘big big boy’ who rescued one of those chocolate chutes for my little sister last Sunday. She was very excited. Thank you for doing that,” said Anna, looking at the boy.

“A pleasure,” said Dirk, “making a tearful little girl very happy. The thing got caught up in a branch of that tree.” He pointed.

“If you are here for a year, will you be going to school then?” Anna wanted to know.

“Yes, I have enrolled in the High School already,” said Dirk. “I hear it’s a boys’ school.”

“And I am unable to attend the same school,” said Alma, a little perplexed. “Why are the High Schools not co-educational?”

“Because you girls beat us up all the time,” said Dirk and backed away just a little.

“The curriculae are quite different in the two systems,” said Anna. “For starters, boys begin with French, Latin and old Greek, while we start with English, and add French and Latin in a couple of years, but you get to drop one eventually. And there are several other differences. What’s more, there are two types of girls’ high schools to choose from. It all depends on what you want to do later, in university. If you’ll need Latin, you have to go to my school.”

“You look awfully young to be in high school already. How old are you?” asked Alma.

“I’m ten. I’ve been there for a month,” said Anna, “since Easter.”

“Well, we won’t need English and French,” said Dirk, “those are our mother languages. We are from Quebec. It’s German that needs a bit of polishing.”

“Your German is excellent. Where did you learn that?”

“Our Dad was born in Germany, came to Canada as a boy,” said Dirk.

“We are talking with two school administrations about me,” said Alma, “to find out what grade I should be in. At home, in Montreal, I had only one more year to go. I may have to take an exam.”

“A cinch,” said her brother, “this beaver knows everything, and I mean EVERYthing.”

“So are we your first new friends, then?”

“Strictly speaking, no,” said Alma.

“Yesterday, I met Karlemann and Petey. They live on either side of us.”

“Who?” asked Dirk, “you flirting already?”

“Yes,” said Alma, “they were just passing by, with a toad in Karlemann’s hand, when I opened the gate.”

“A toad?”

“Yes. They were getting a knife to open it and see what’s inside,” said Alma.

“How old are these guys?” asked Dirk. Alma looked at Anna.

“Four or five,” she said, “they’re so cute. What did you do?”

“I took the toad and sat at Petey’s sandbox with them,” Alma said. “I explained that it would hurt the toad if they opened it. But I drew an interior map of a toad in the sand.” Dirk twirled on his skates, laughing.

“My sister doesn’t know the first thing about toads,” he said.

“Hey! I thought you said she knows everything?” said Anna. “Were the boys satisfied?”

“I think so, except they had expected a small motor in there. And they were intrigued by the anus. Didn’t know toads needed to poop.”

Dirk attempted another twirl but performed an attractive pratfall instead. Still laughing.

Dirk would always smile, often clown, whereas Alma didn’t seem to have to do anything. She just was, her fluid motions, high neck, long limbs and pleasant low voice drawing everyone’s attention to her the moment she came into view. Except she didn’t seem to notice. For the next five years, all the girls aged ten to fourteen strove to look, walk and talk just like Alma, moved strands of hair away from their temples with their fingertips, hitched skirts and pulled up knee highs, sliding thumb away down inside the socks before bringing them up again, and pensively sucking the tip of their little fingers, the way Alma did on occasion. Every girl wanted a Holland bike with thick strong tires, just like Alma’s.

Dirk skated away now, chased by his sister. Before turning onto the sidewalk up at the corner they waved to Anna.

After dinner she went out and helped Father dig dried horse manure into the soil around his beloved rhododendrons. Korinna looked on, chewing her nails.

“I met your new big friend this afternoon,” said Anna, “the one who picked your chocolates out of the tree for you. His name is Dirk. You’re right. He IS very nice. And he has an even bigger sister.”

“What’s her name?” asked Korinna.

“Um, I can’t remember, except it doesn’t sound like her, that name. They are from Canada. Did he tell you?”

“No. If you can’t remember her name, why don’t you call her ‘Canada’? Everybody will remember THAT.” Sensible five year old.

This is how everybody remembered Alma acquiring her new name, one she liked a lot better than her own.

That night Anna got out her movie star collection, the photos found in cigarette packs, methodically and passionately traded by girls between the ages of ten and fourteen, Anna always at a disadvantage because no one smoked at their house. She was looking for an actress who reminded her of Alma, those soft brown eyes, gentle cheekbones and perfectly even white teeth. Who was it? Who? LaJana? No. Pola Negri? No. Finally she gave up and went to bed. Tomorrow she would try to draw a portrait of ‘Canada.’

In August, Anna was going to join Tante Marianne and Uncle Robert for a first summer vacation away from home. Mother had packed a new bathing suit and cap, a wide fitting skirt and blouse and sandals. The younger sisters were to visit the grandparents with Father.

Uncle Robert picked her up at the small station, surrounded by sand and weeds, and when he led her back to the car she found two big noisy boys in the back seat. Within seconds she discovered that she was not the only child sharing her aunt and uncle’s vacation, but Huck and Bobbie were to be along for the entire time, and her heart sank. Huck immediately began to pull little strands of hair out of her neat braids, and Bobbie cackled like a barn full of hens. When the new ties had been loosened and her hair was blowing all over the place, her hands by the side of her head, Anna turned and said, “I don’t care for that stuff, you know.”

Uncle laughed.

“Now boys, we mustn’t make a bad impression right off the bat,” he said, “we want to behave ourselves, don’t we?”

They didn’t. They lifted her sun hat and pretended to fling it out the window, then brought it around and plopped it back on her head.

Cackles.

“Oh my, it IS windy out there, isn’t it?” said Tante Marianne and folded Anna into her arms. “Come, I’ll show you your room.”

The rented cottage was immense, with decks at the front and back, a huge, sunny kitchen — and outdoor plumbing. No real bathroom, that is.

But the sea could be heard, as well as shrieking gulls, from every corner of the house.

Less than three minutes away, beyond the dunes, there was the most magical beach, with shells and driftwood washed up by a gentle Baltic Sea tide, and with clean sand and funny birds.

It seemed like paradise. Paradise with two fat poltergeists who had to get up early to accompany Uncle Robert on his morning runs along the dunes, who played soccer (goal being two cow pads, thoughtfully dropped just the right distance apart), and who were a gigantic nuisance whenever they came back for meals. Uncle challenged Anna one morning to come out and play, like the big kids, and she returned an hour later, her arm covered in cow dung, except that, in role as goalie, she had caught the ball. Uncle related the incident with an air of merriment and left her with Tante Marianne and ‘the girl’ who came every day to do chores.

Tante Marianne didn’t go swimming or even bathing with the rest of them, feeling “a little out of sorts this year”. She had brought books instead, and a basket full of knitting wool, and was making baby booties, little jackets, hats, in white and yellow. For a friend.

Anna read ‘Gone with the Wind,’ ‘Unordnung und frühes Leid,’ (Disorder and early Sorrow,) and ‘Jalna’. Tante Marianne, a paedriatic nurse by training, brushed up on baby care. For the friend.

Huck and Bobbie hid a worm on Anna’s pillow, soaked her sandals in the rain barrel and put sand in her sandwich.

“Ignore them,” advised Tante Marianne, but before she learned to do that convincingly, the big day arrived, when they were to board the huge ferry to spend the day on the island. They drove over to the next town, and joined the crowd that was lining up on a long pier, reaching away out into the ocean to the deep water, where the ferry would dock.

The boys were climbing in and out of the sturdy wood railing, swinging outside, pretending to be afraid of dropping the thirty odd feet into the water, when it happened. A small child next to Uncle, having repeated Huck and Bobbie’s antics, slipped and dropped from the bridge. He surfaced a moment later, screaming and thrashing, and gulping water. The crowd stood frozen for just a moment, then people at the rear turned and pushed to run back to the beach. The parents were shouting and waving their arms for someone to do something. Anna, close to the railing, had already slipped off her sandals and climbed out to the ledge. The boy was just bobbing and kicking and drifting under the bridge when she jumped.

She landed a few feet from him, shot straight to the bottom, and grabbed his shirt as soon as she surfaced. Anna had been a strong swimmer for several years but she wasn’t prepared for the energy of a wildly panic-stricken toddler. Someone dropped a ring attached to a line, but she couldn’t get close to it. She was vaguely aware of a huge cloud of noise above them, and kept kicking, working to keep the child’s face above the water line. Just as she began to feel solid ground below her feet, a big shadow stood over her, and an immense life guard picked her and the toddler out of the waves washing towards the beach.

The crowd was divided between those who were irritated for having their nerves rattled without warning, ones who resented the delay in the ferry’s punctual departure, and the jolly folks who just stood smiling with relief at a happy ending.

Tante Marianne, Uncle Robert and the poltergeists didn’t mind admitting ownership of the young heroine presently receiving the stunning ovation, and even smiled while deciding that this wasn’t the day for an island picnic after all, seeing she was wet as a seal and a chilly wind had come up.

“Like wrestling a baby octopus,” Anna grinned, shivering and dripping all over the car.

For the rest of their vacation Anna was left alone to read her books in the sand dunes.

And though for some weeks she had been battling two other guests of the male pest persuasion, who initially escaped punishment, she had had a good time.

“So how were the holidays?” asked Canada after her return to Berlin. And Anna had prepared “splendid” as the appropriate term.

“Yours?”

“Well, my parents are thinking seriously about returning home,” said Canada. “It’s just a little unsettling. Dad thinks there will be a war. We may leave in a couple of weeks.”

“Oh no! We’d all miss you.”

The Brauns didn’t leave then. But three weeks later, on September 1, 1939, the German army marched into Poland. “…Finally returned the fire!” as a government spokesman had put it.

Anna’s, Nadja’s and Korinna’s father, a reserve officer in a Royal Bavarian Cavalry regiment since the World War, put on his uniform and left for the front.

Anna finds sheets of lined paper folded in a large gray weather-beaten envelope. She recognizes her own childhood writing in Sytterlin, the old Gothic style. Done in ink, pale now, but still legible, on thin green paper. Lines crossed out, words replaced, and sentences re-phrased.

“April 20, 1945, Berlin,” Anna reads, and centred on the page,

“MY LAST WILL AND TESTAMENT.”

She gets up.

“I have to go to the loo,” she says, and leaves, the page crumpled in her fist.

“Anna —” The sisters are at the door. “You have been in there an awfully long time. Why not come out now. We’ve just made some tea.”

“I don’t need tea. I need a bucket. Just leave me.”

“Is this a Canadian thing, this not crying in public, do you think?” They are back in the room.

“No,” says Korinna, “it’s an Anna thing. Don’t you remember? She always figured she couldn’t afford to float away in a puddle when something was coming apart at the seams. She’s the oldest, after all. She always believed it meant she couldn’t cry, not openly. Don’t you remember?”

“Hmmm. Did you see what it was she found in Mother’s folder?”

“No.”

“We ought to keep THIS aside then for the moment. Look. It’s a kind of baby diary Mother kept about us. Smell it. Mouse pee?”

“Yikes! From the Berlin storage, I bet. It won’t come out either.”

“Here is one of her little zip-lock bags. Put it in there. We can keep it in my purse, no, yours, for now.”

“Korinna? In a few months let’s get together and read the diary.”

“Here she comes I think. Get the tea.”

Having disposed of the offending page, with repeated pokes of the brush and wadded toilet paper, Anna, her face washed and her composure restored, is back.

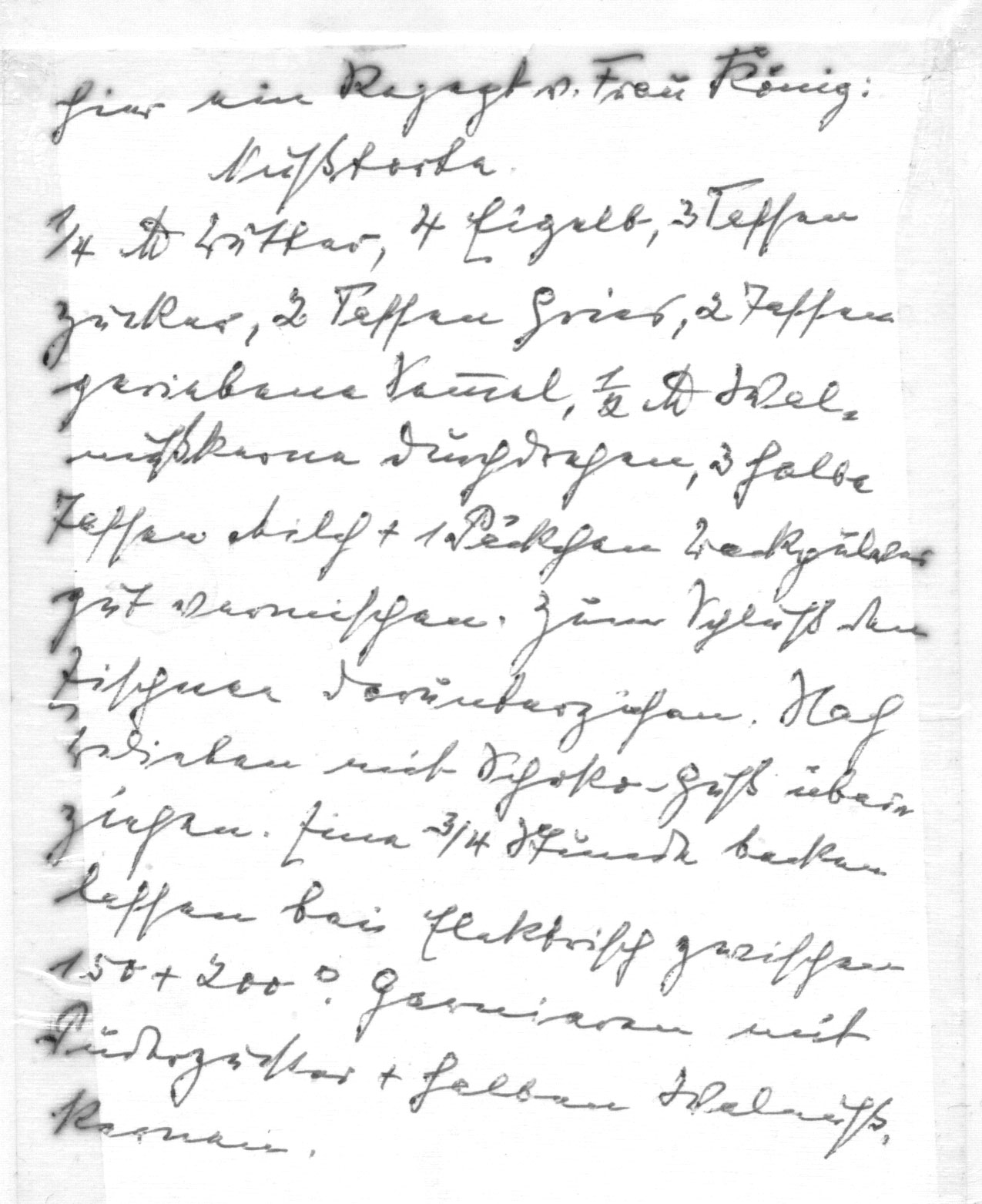

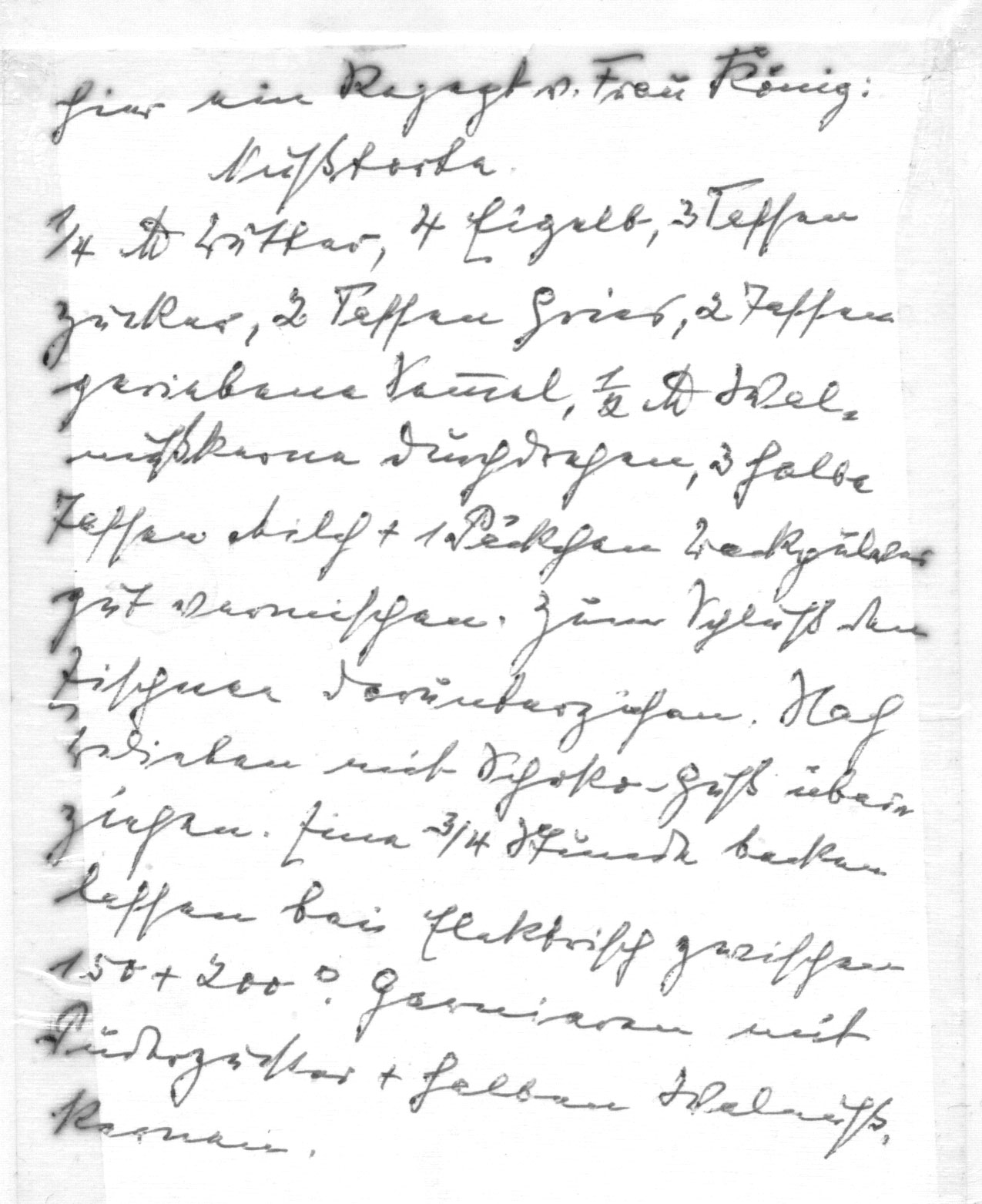

“Look at this: Mother’s handwritten recipe for her Nusstorte!”

Anna closes the door behind her.

“I want a photocopy,” she says.